Perverse Incentives in Complex Systems

Taking lessons from history to prevent getting more of what you DO NOT want

Once upon a time, not so long long ago, India was under British rule. There was one thing though, that haunted the British - the venomous cobras slithering around the city and scaring people in the beautiful town of Delhi. The British government decided to take action to rectify the problem. The government offered citizens a financial incentive to redeem dead cobras. While this was a good short-term solution, the entrepreneurial Indian citizens started to breed cobras. Cobra breeders killed most of the cobras and redeemed them for money while they continued to breed more cobras. The government eventually found out about this loophole and stopped the financial incentives. Later, the cobra breeders released the snakes back to the streets since they were not valuable to them anymore. Sadly, it made the cobra problem worse than it was when it started.

Most of you would have read this somewhere - most probably in some LinkedIn post with a completely unrelated “life lesson” at the end. But this anecdote (possibly ahistorical), popularly known as the Cobra effect was (coined by economist Horst Siebert) is one of the most direct examples of Perverse Incentive Theory. The perverse incentive theory has far reaching applications – in public policy, Industrial relations, team management or even working with your domestic help.

In the simplest terms - A perverse incentive is an incentive that has an unintended and undesirable result which is contrary to the interests of the incentive makers. But before we jump ahead, there is one important clarification. The incentive in the Perverse Incentive denotes both incentive and disincentives ( i.e. both rewards and punishments). Not only can rewarding go wrong, but punishments can also push the wrong buttons.

Where do we go wrong?

In the hindsight, the problem seems evident, doesn’t it? How could they not anticipate that?

Well, they didn’t, neither would we, because we are all in search for simplicity in one grand solution, one big idea that will change the world. Instead, it is one big ecosystem with interdependencies that we can only try to grasp. No wonder people don’t understand the problem with animal extinctions. To structure this, the most common pitfalls that lead to Perverse Incentives are

Modularity: When we look at problems, or functions or departments in isolation, and try to fix the issues there, without considering the effects they might have on the other parts. For ex. A Quality Assurance team that is given the task to identify defects and stop production immediately, will focus on stopping production rather that solving the problem.

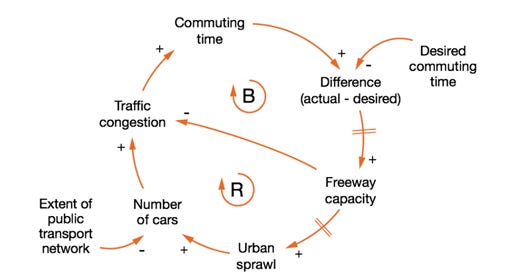

Band-aid approach / firefighting: When short-term fixes are applied, without looking at how they might affect the longer term and without considering the second order effects. Look at the system model below, on how a freeway – built to reduce traffic congestion may end up increasing it in the longer run.

Wrong measures / metrics: Will explain this through just two very self-explanatory anecdotes.

During the deportation of criminals from Great Britain to Australia, the transport companies were compensated based on the number of prisoners shipped, not the number delivered. There was therefore no economic reason to keep them alive on the boats and a large percentage of the prisoners consequently perished on-board.

In another well-known incident, IBM implemented a pay structure that paid their computer programmers by the line for the code they wrote. Their goal was to increase the quality of the code. As a result, the programmers found ways to unnecessarily maximize the line count, increasing their pay and reducing the quality of the code.

The long fix

There are many problems, that will be unanticipated. In public policy, they are commonly known as “Policy Surprises”. While you may try to think through to avoid the above pitfalls, there are some that one cannot foresee.

There was a car manufacturing setup, a standard assembly line one where the workers were paid for every car they completed. Sometimes due to technical failures the line would stop for breakdowns. Even though they tried their best to reduce breakdowns, any breakdown would lead to loss of worker’s time and they would get lesser pay. They pleaded to get compensated, and the management obliged. The management decided to compensate for any downtime related to technical breakdown. Everyone was happy, the system worked perfectly, until the notoriety slowly began to set-in. Eventually the workers, who got a taste of the free money would turn to bad working practices to increase wear and tear, and downtimes, so that they can earn money – sitting and waiting for breakdowns to get repaired.

All three pitfalls were to be seen here – modularity, band-aid fix, and wrong measure of output. All possibly too evasive to predict at the start.

Therefore, the one last ingredient in this entire wheel of incentives is - good feedback systems. It is very important to spend a lot of effort setup a feedback system that can capture the inherent dynamics of systems we work in.

The perverse incentive theory blames no one. It is a historical reminder for us, to create better systems, become better parents and deal with our work a little better.

Also, we wouldn’t want you to later look back and regret not subscribing to our articles, so here’s the link to subscribe to our posts