Looking back at the first year of our MBA, I remember how cumbersome case studies would get. Long cases spanning 15-20 pages would take upwards an hour, and you could see some groups with highlighters in their hand carefully highlighting parts of the cases. Fast forward to the second year – where the entire class had acquired a superpower – we could make sense of all those cases, even as we skimmed through them 5 min before the class. We didn’t become super intelligent in a span of 12 months, instead we had built a super skill – eliminating the noise. Every case would have tons of unrelated info, and you build the skill of knowing where the actual juicy part is.

Disclaimer: We don’t recommend taking real life decisions by skimming through the scenario. But we do recommend eliminating noise.

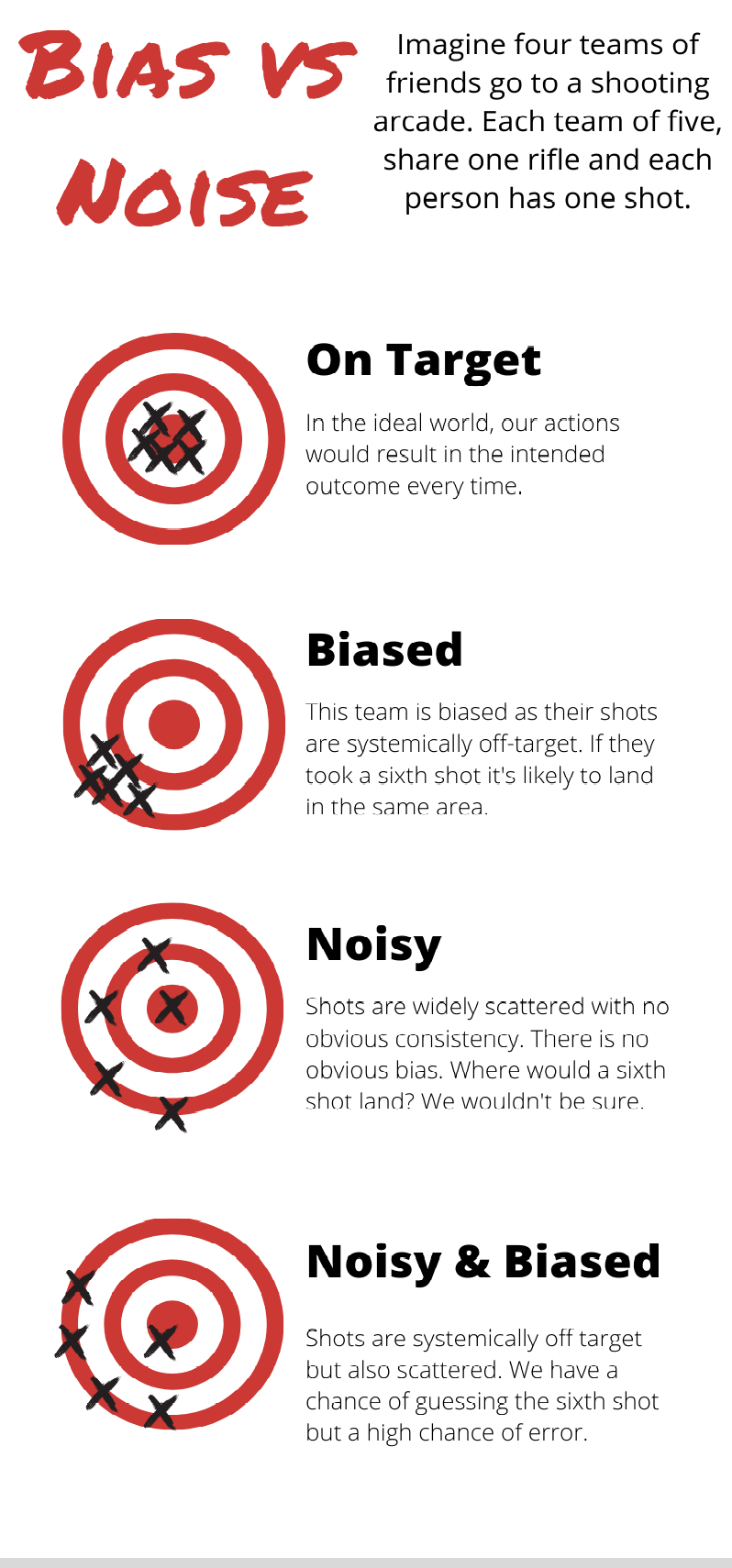

What is Noise?

Humans are unreliable decision makers; their judgments are strongly influenced by irrelevant factors, such as their current mood, the time since their last meal, and the weather. This chance variability of judgments is call Noise.

Wait. Then what is bias? Bias are systematic errors in judgement. To put it simply, biases are consistent errors in out judgement, and they can be easily identified and offsetting them is also easy. For ex: there is a throwing game which typically favours the right-handed participants because of the design of the game – the game is biased. But that bias can be offset by providing left-handed participants extra points by default.

Where do we see noise in our professional lives? Some jobs are noise-free. Clerks at a bank or a post office perform complex tasks, but they must follow strict rules that limit subjective judgment and guarantee, by design, that identical cases will be treated identically. In contrast, medical professionals, loan officers, project managers, judges, and executives all make judgment calls, which are guided by informal experience and general principles rather than by rigid rules. Basically, the higher the judgement involved, the fatter the pay check gets.

Where there is judgment, there is noise

The very concept of judgment involves a reluctant acknowledgement that you can never be certain that a judgment is right. But we shouldn’t confuse judgment with preference. In an opinion or preference, it is matter what is best suited for you given your experience. In judgement, it is a matter of what is best suited for all concerned stakeholders.

The issue of this noise – consistency of decision might seem important in professions like criminal punishments, consultancy solutions, or hiring decisions. But they are equally important while taking decisions while making a change at that manufacturing line or responding to sales query from a distributor.

At a global financial services firm, a longtime customer accidentally submitted the same application file to two offices. Though the employees who reviewed the file were supposed to follow the same guidelines—and thus arrive at similar outcomes—the separate offices returned very different quotes. Taken aback, the customer gave the business to a competitor.

Any professional service if seen as unreliable, will start sinking faster than crypto after Musk’s tweets.

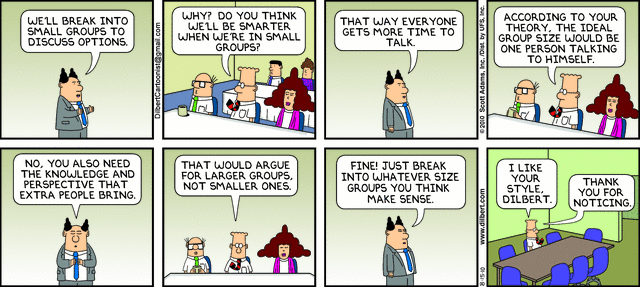

Groupthink

In an attempt to reduce the biases and noise, many organisations resort to group judgements. The idea is that this would offset bias and reduce variability to a large extent. Interview panels, trial juries are all implementations of this idea. But are groups immune to noise? In a large scale experiment of music downloads, very interesting insights were discovered by Matthew Salganik and his co-authors.

The experimenters created a control group of thousands of people (visitors to a moderately popular website). Members of the control group could hear and download one or more of seventy-two songs by new bands.

In the control group, the participants were told nothing about what anyone else had said or done. They were left to make their own independent judgments about which songs they liked and wished to download. But Salganik and his colleagues also created eight other groups, to which thousands of other website visitors were randomly assigned. For members of those groups, everything was the same, with just one exception: people could see how many people in their particular group had previously downloaded every individual song.

You might well predict that in the end, the good songs would always rise to the top and the bad ones would always sink to the bottom. If so, the various groups would end up with identical or at least similar rankings. Across groups, there would be no noise.

The key finding was that group rankings were wildly disparate: across different groups, there was a great deal of noise. Result: A successful song in one group would be a disaster in other groups and vice-versa.

Two insights from the experiment were:

If a song benefited from early popularity, it could do really well. If it did not get that benefit, the outcome could be very different – the impact of Social Influence

The very worst songs (as established by the control group) never ended up at the very top, and the very best songs never ended up at the very bottom.

While groups provide a certain level of sanity, they are not noise free. Specially if it is about picking “the best”, the decision might be equally noisy as an individual judgement. This is can be caused by groupthink, or HiPPO.

Bringing discipline to judgment

If one were to ask, how to best eliminate noise – the answer would be to bring in algorithms. But the transition is costly, they would still require human monitoring and more importantly even algorithms have shown biases.

In the book Noise, by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, Cass Sunstein, the authors prescribe 6 principles to reduce noise:

Accept that decisions are about accuracy, not individual expression.

Your opinion and preference is fine, but this is about accuracy not validation.

Think statistically, and take an outside view of the problem.

We think that our experience teaches us to take the best decisions. But if we were to put down all experiences into a log book and analyse it to take decisions, we would be better off.

Structure judgement into independent tasks

Look at parts of decision making independently, as one might carry forward the intent of one part into another.

Decision-makers should resist premature intuitions.

Well, obviously yes. But repeating the obvious has its merits.

Take independent judgements from multiple judges and factor them in.

Take judgements from multiple people, but individually, that way you can do away with social influence.

Favour relative judgements, which tend to be less noisy.

Absolute judgements are a fallacy.

Practically, any firm whose employees exercise judgment does not expect decisions to be entirely free of noise. But often noise is far above the level that executives would consider tolerable—and they are completely unaware of it. The entire effort of bringing this concept of Noise to our work and our life otherwise, is to reduce it to as minimal as possible.

If we can reduce the noise, we might make way for the music.