In order for different processes to share the CPU, computers perform what is known as a context switch. This is where they store the current state of a process, switch to a different process and come back to resume the previous task. It is notable that the process of context switching can have a negative impact on system performance. Today we are going to look at one of the biggest threats to performance and engagement of remote teams: context switching. In an age where attention is the most scarce resource, it has never been easier for our brains to rapidly switch between unrelated processes during the course of a work day. Understanding the psychology of context / task switching can hence help us assess and improve how we approach work.

If I have made any valuable discoveries, it has been owing more to patient attention than to any other talent

Isaac Newton

The perception of multitasking

We tend to define multitasking as being engaged in different processes concurrently. Research has shown that this is not very accurate, that we actually do not work on different tasks at the same time but rather rapidly switch between different tasks at hand. Effectively we do not attend to more than one task at any given point of time. It is also interesting to note how people perceive the same task as either single tasking or multi tasking. For instance you could perceive attending a meeting as a single task but you could be listening and taking notes at the same time. The mere illusion of multi tasking and its perception might impact performance, engagement and experience. This is the most surprising find of this study. Keeping aside the fact that multi tasking may diminish performance, making people feel that they are performing a multi tasking activity increases engagement with the activity and benefits performance.

So it all comes down to how you define the activity. Let’s say you are watching two different football matches on a split screen. Are you single tasking or multi tasking? If you define your activity broadly as ‘watching sports’ then you are more likely to feel that you are single tasking. What if you now have to watch both the games on different devices? Does this change your perception of the nature of the activity? So breaking down a complex activity and helping people define their tasks this way to increase the perception of multitasking can go a long way in increasing their engagement.

While other analyses conducted on this topic examined how asking individuals to do more hurts performance, we hold the activity constant and focus on the mere effect of multitasking perceptions

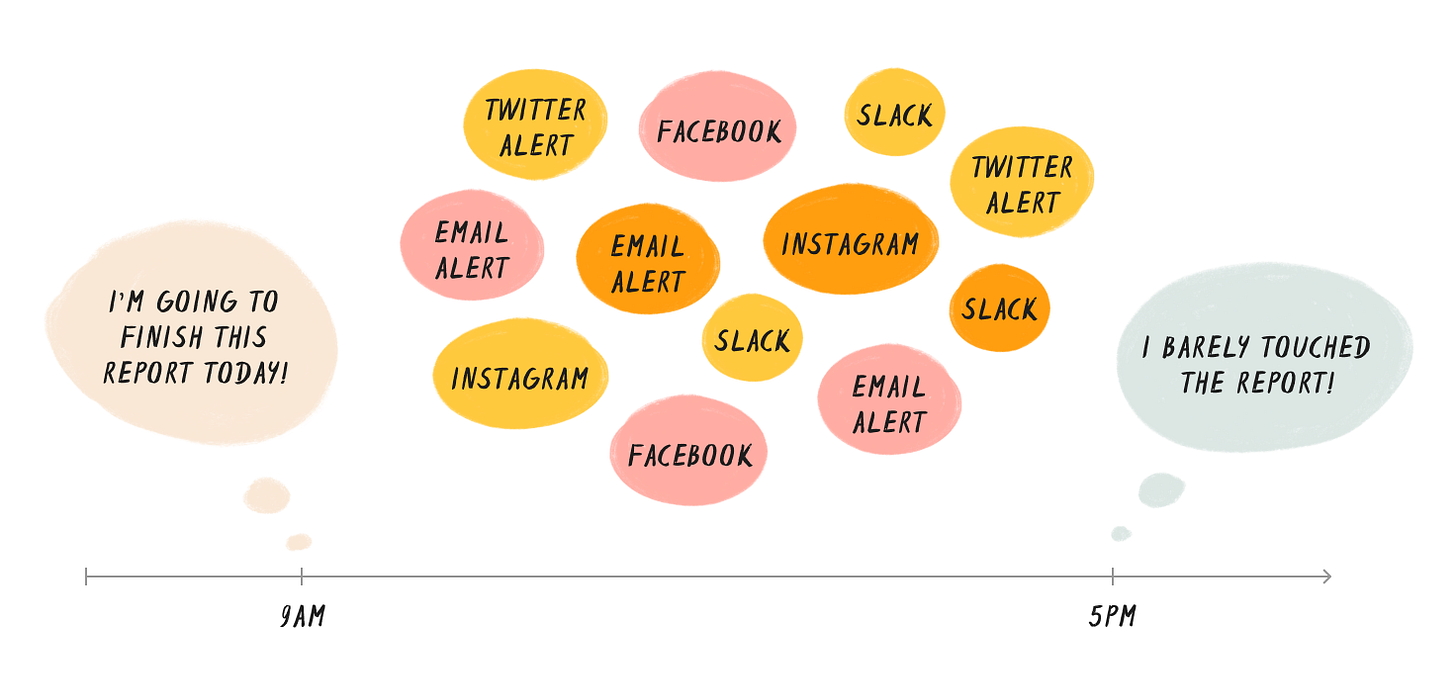

The cost of switching

Here is how the cost of switching is measured. Let’s say you are performing a task A and you are asked to switch to task B. The difference in accuracy / performance between performing a repeat task (A-A) and a switch task (A-B) is the switch cost. This factors in the attention residue after switching a task which is the true cost of rapid context switching. The modern workplace is designed to disrupt. In spite of the popular notion that software is eating the world, enterprise software is still broken. Studies show how the average number of apps used by businesses has shot up by over 43% over the last few years and the average executive has gone from sending and receiving about 1,000 communications per year to over 30,000 today, or one every four minutes. This has inevitably led to an explosion in the number of screen switches one goes through in a day. Enterprise software solutions hence need to find ways of defragmenting the user experience in order to not cause pain to everyone involved.

The psychology of satisfaction

Going back to the computing analogy, switching between threads of a single process can be much faster than between two unrelated processes. Context switching does not hinder performance if the task involves identifying a pattern between the seemingly unrelated tasks. This aside, the most cost intensive switcheroos - the ones not pertaining to the work at hand arise from a state of dissatisfaction. Nir explains in his book Indistractable that the four psychological factors making satisfaction temporary are as follows:

Boredom - people prefer doing to thinking

Negativity Bias - good things are nice, but bad things can kill you, which is why we pay attention to and remember the bad stuff first

Rumination - the process of continuously thinking about bad stuff

Hedonic Adaptation - the tendency to quickly return to a baseline level of satisfaction, no matter what happens to us in life. All sorts of life events we think would make us happier actually don’t, or at least they don’t for very long

Our inclination towards these factors (from evolutionary adaptation) ensure that we never stay satisfied for too long. This translates to behaviours taking the form of checking email and social media way longer than necessary. Knowing the cost of a context switch still does not help avoid it, but understanding that its root cause is poor management of pain and satisfaction helps better defragment our calendars.