Assessing Self-Image

A lot has been written about how to give feedback but not much about how to get useful feedback from others and effectively using it.

“The only true wisdom is to know that you know nothing”

-Socrates

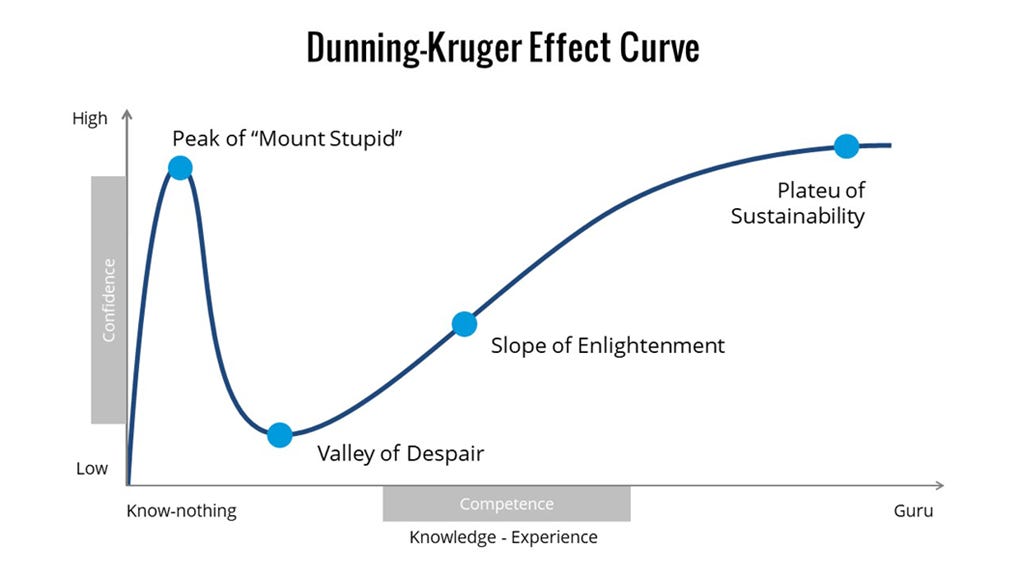

As a young enthusiastic intern, I walked into the office beaming with pride at the project I had received. It seemed really cool, very fancy and of strategic importance. I knew I was equipped with all related frameworks, research papers and questionnaires. If I could time-travel, I would probably just hand my past self this photo with the caption “You are right at the top of Mount Stupid”.

The Dunning-Kruger effect captures our competence and confidence cycle. When ever we begin our learning journey - a new job, or a new domain of work we start with overestimating ability to succeed. It’s our journey from being naïve and cocky and then gliding down to self-doubt and then gradually building up.

In the hindsight, we can always piece together what stage we were at, but in the present it’s just as good guess. Imagine this has been your growth so far:

But then you could be anywhere.

Here:

Here:

Or here:

Ignore my sketching skills (I am thankfully very self-aware of that), you probably get the point. And the solution to this conundrum is very very simple, but extremely difficult to practice: Getting feedback.

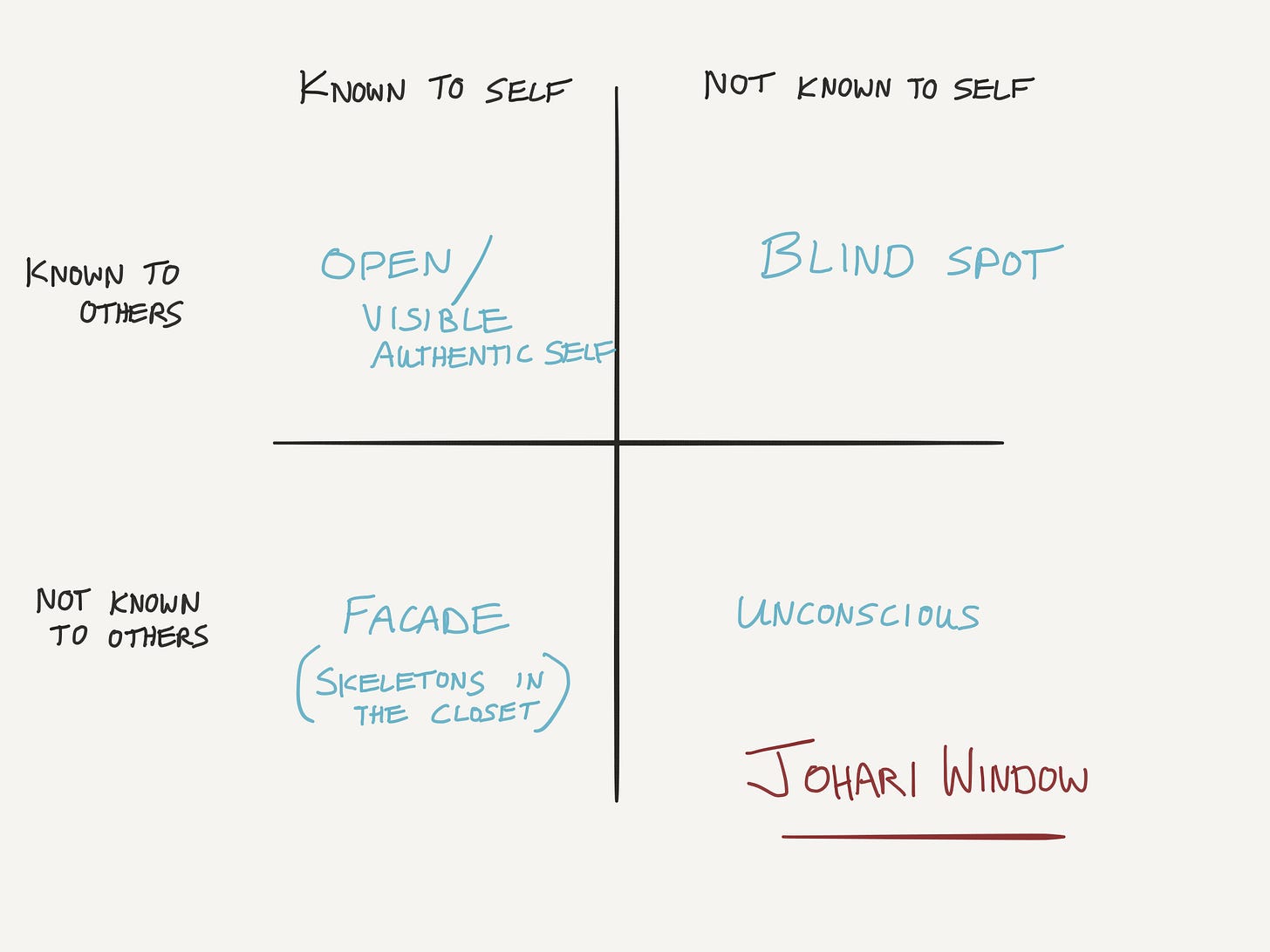

Defensive Reasoning

It is fascinating to know how little we seem to know about ourselves. As we all have a visual blind spot of which we aren't aware until someone points it out, we have mental blind spots of which we aren't aware as well. Unlike being shown how objects can be made to disappear behind our visual blind spot, however, having truths pointed out to us that hide behind our mental blind spots isn't necessarily accompanied by a joyful sense of discovery. You could certainly try it out for yourself using the Johari window exercise. The “Blind Spot” quadrant would have some surprises for you.

A lot has been written about how to give feedback but not much about how to get useful feedback from others. It can be hard to draw out the truth from the people around you and even more difficult to swallow it. We are hard-wired with the self serving bias, and no matter how open minded we are, we might resort to being defensive.

Everyone develops a theory of action—a set of rules that individuals use to design and implement their own behavior as well as to understand the behavior of others. Most theories-in-use rest on the same set of governing values. There is a universal human tendency to design one’s actions consistently according to four basic values:

1. To remain in unilateral control;

2. To maximize “winning” and minimize “losing”;

3. To suppress negative feelings; and

4. To be as “rational” as possible—by which people mean defining clear objectives and evaluating their behavior in terms of whether or not they have achieved them.

The purpose of all these values is to avoid embarrassment or threat, feeling vulnerable or incompetent. Basically, our logical brains evolved mainly to help our limbic brain with social validation and likability (since being in a collective was important for survival), and not to pour ourselves over Advanced Calculus.

This hard-wiring leads us to defensive reasoning. Defensive reasoning encourages individuals to keep private the premises, inferences, and conclusions that shape their behavior and to avoid testing them in a truly independent, objective fashion.

The art of feedback

Now that we have established why and how we get defensive while getting feedback, we also need to get going on the feedback. To get the feedback is one thing, but to process it and act on it, another. Just like with storytelling and negotiation, there is some very insightful and impactful work done on art of feedback.

1. Resisting the flight or fight

As part of a research program for the book, Insight, dozens of interviews were conducted with people who’d made dramatic improvements in their self-awareness. These were the participants who had frequently sought critical feedback that would help them improve. But they weren’t necessarily fond of the experience. One participant, quipped, “Are you kidding? I hate hearing that I’m not perfect!”. Nobody does.

This can be solved through self-affirmation. Taking a few minutes to remind ourselves of other aspects of our identity, besides the one being threatened, lessens our physical response to threat and helps us be more open to critical feedback.

Ex. If you’ve learned your team sees you as a micromanager, you might remind yourself that you’re a supportive friend, devoted community member, or loving parent.

2. Opinion, not a fact

Once we practice taking in the feedback without reacting it immediately, the next step is validation. Feedback puts up is an area of self-doubt, often forgetting the fact that everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact.

When we hear something new, it’s a good idea to ask a few trustworthy sources whether they’ve noticed the same behavior. I would statistically recommend checking with 30 or more people, but 2-3 should do the trick.

3. A little showmanship

Even when we’ve significantly improved a certain behavior, it doesn’t mean that the people around us will automatically notice. It is harder to change the perceptions of our behavior than the behavior itself. Spend energy improving based on feedback, but they don’t notice it? Discouraging.

Shortly after receiving their feedback report, choose one highly visible and symbolic action that will show how serious you are about changing.

Paul, who ran the radiology department in a large regional medical center was seen to be as a boss who didn’t care about their day-to-day challenges, which was frustrating and demoralizing. A few weeks prior, the doorstop in the entrance to the radiology department had broken off. Employees transporting patients in stretchers had to precariously prop the door open with their hip and quickly squeeze the stretcher through before it closed. The plan that Paul created contained many excellent, longer-term strategies to gain his team’s trust. But before he even started executing it, we selected his harbinger. He walked down to the department during the busiest time of the day and, in plain view, replace the doorstop with his own hands. Paul’s employees immediately noticed and appreciated this symbolic step, which made it far easier to spot the other changes he made moving forward.

4. It’s not awkward

Research by Francesca Gino, Paul Green, and Brad Staats has shown that we tend to avoid people after they give us negative feedback. if you are dramatic, you might even build stories in your head and see yourself as the aggrieved party in a vast workplace conspiracy, but isolating yourself from people who tell us the truth is a big mistake.

Contrarily, critical feedback can be an excellent excuse to reset our relationships. After a conflict, seeking feedback and trying to reset expectations moving forward is a sure-shot win, if you manage to take the first step.

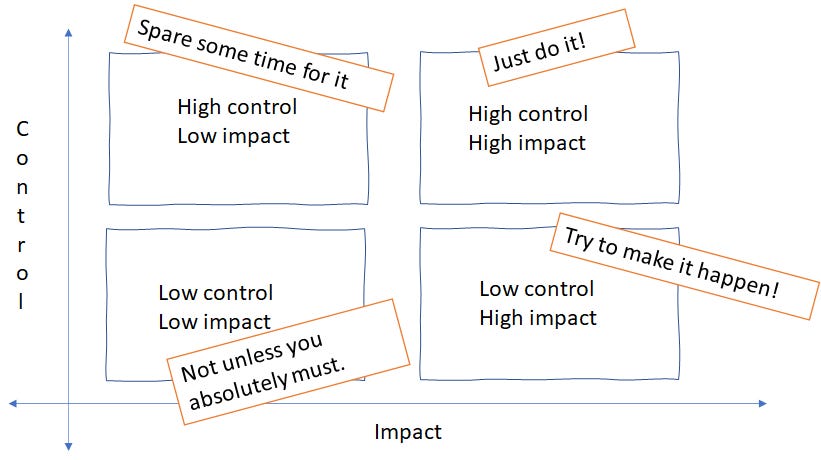

5. Option 0: Do nothing

The best way to manage our weaknesses isn’t always clear cut. Sometimes feedback can illuminate flaws that are tightly woven into the very fabric of who we are. When we let go of the things we cannot change, it frees up the energy to focus on changing the things we can. Maybe a little control-impact matrix would help.

Keep digging

Introspection isn’t the best way to know yourself. You are just watching yourself, tell yourself, what you already know and think about yourself. So go reach out to your true critics and surprise yourself.

We would love to hear your feedback on our content too. Please write to us at creators@idealgas.in